Of All the Things Jay Taught Me

Jay Caguiat lived like he couldn’t wait to die, and he was my best friend.

He was hired as a cook at the restaurant where I worked my first job as a dishwasher. He was quiet back then. Reserved. The roiling compulsion for debauchery that I came to know as a hallmark of his personality had yet to be revealed. He was also one of the hardest workers I had ever met. Within four months he was promoted to kitchen manager.

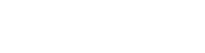

We would close the kitchen together five nights a week, hardly speaking to one another at first. I was 17. Still in high school. I worked well past midnight most nights and hardly bothered getting up for school the next day. I was barely passing. I didn’t care.

One Thursday night, after a particularly gruelling shift, Jay was blasting a Pixies song on the beat-up kitchen stereo.

“Don’t suppose you know where a guy can buy weed around here, do you?” Jay said without looking at me. It was the first thing he ever said to me outside the context of the restaurant.

“I um…yeah. I have some on me, actually,” I said. I was a fledgling dealer at the time, selling just enough to afford my own habit.

Jay slapped a $20 bill between us on the stainless-steel prep counter.

“I’ll finish up here,” he said, “you go roll us a couple of joints. I have beers chilling in the walk-in.”

To this day I have no idea what it was that made him take a shine to me, but that’s how it all started. Most nights after work we would get high and drink strong, bitter beer while we walked the streets of sleepy suburbs. He was 12 years older than me but addressed me as a peer.

He taught me the ins and outs of the line, how to handle busy nights, and how to prep a kitchen to streamline the entire commercial cooking process. Before long, I went from being a dishwasher to lead cook. Jay’s second-in-command. I barely graduated high school. It didn’t matter.

After a couple years, Jay landed a new job at a much nicer restaurant in the more affluent part of town and brought me along. We quickly became favourites among the staff and owner. A veritable “dream team”. By then, joints and beers had given way to hard drugs, hallucinogens, and liquor. “Running on heavy fuel”, Jay called it. I barely slept between nights out and early shifts the following day. The bags under my sunken eyes grew more shaded, the plum colour of fresh bruises. The tremble in my hands was constant. If Jay felt the same, he was better at hiding it, or so I thought.

One day I came in to work find Jay had been sent home after passing out on the staff washroom floor. We laughed about it later, but something stirred in me. If I worked the morning shift that day I’d likely be in the same position. Or worse. The discomfort of consequence crept into me. I felt like a motorcyclist rolling by a bad wreck with no helmet on.

The atmosphere at work had also changed. The dead-man-walking glares Jay received were reflected onto me by association. As a 20-year-old with no prospects, the idea of getting fired for letting my vices get the better of me was a shame I had no desire to bear. On a smoke break, I told Jay we’d have to limit our post-work adventures to Sundays and Mondays. He flicked his cigarette into the chest of my apron and went back inside. I took no offense.

I kept my head down, did my job, eased up on the boozing and only dabbled in harder stuff at the end of the work week. I felt better. My performance at work improved. The staff warmed up to me again. Jay didn’t follow my lead.

It was a Saturday morning. Jay had no-showed. The owner of the restaurant was grilling me about what we did the night before. I calmly explained that I didn’t go out, that Jay was an adult, that we weren’t joined at the hip. I scrambled to set up Jay’s station on top of my own, mentally preparing to be put through the wringer for the next 12 hours.

Around 4 p.m. Jay burst into the staff entrance, covered in mud and scratched up like he had wrestled a rosebush. He spotted me and stomped over in his dirt-stained shorts and hoodie. Grabbing my shoulders, he hunched down, putting his face inches from my own. His eyes were all pupil. Wide, black, and crazed. His breath carried the acrid aldehyde stench of a man who had completely unravelled.

“Bipedal bears are chasing me,” he said, with such conviction that I looked over his shoulder, half-expecting to see upright bears lumbering in through the kitchen door.

“Holy fuck, Jay,” I said, “this is not a good look.”

Before I could say more, the owner of the restaurant walked in, took one look at Jay and bellowed “Caguiat, get the fuck out of my restaurant! You’re fucking fired! I’ll mail your goddamn paycheque!”

Jay let go of my shoulders and took a few steps back without taking his eyes off me, then he spun around and rushed out the door, his shoulder hitting the jamb on the way out and knocking him off balance. I pulled my cap down, picked up my knife, and got back to work. I didn’t say a word for the next 8 hours.

Jay’s episode, it turned out, was the result of an acid trip mixed with cocaine-induced paranoid psychosis and God knows what else. When I spoke to him a few days later he barely remembered anything, but he knew he was unemployed. We were drinking warm beer in a cold park.

“I’m gonna need your help until I find something,” Jay said.

“Whatever you need, man, just name it,” I said. I felt like I owed him.

“I need $1500 to see me through for a bit,” he said.

“Jesus…that’s pretty steep, man.”

“I know, I know, but I have bills and shit and I’m already a little behind.”

“A little behind? A grand and a half isn’t ‘a little behind’, Jay. What’s up?”

“Alright I’ll level with you, little brother. I pay child support, and I can’t fall behind.”

I had known Jay nearly three years. He never mentioned he was a father. I let the silence envelope us, hoping it would squeeze more out of him.

“My daughter, Darcy. She’ll be 6 next month. I need this, man. I wouldn’t ask if I wasn’t desperate.”

I gave him $200 cash right there and signed my next paycheque over to him, but my admiration for him evaporated. I now saw a man going to insane lengths to numb himself to the pressures of responsibility. Jay taught me a lot in the time I knew him, but if I took one thing away from our relationship, it was that living like you couldn’t wait to die just meant you were terrified of growing up.

Leave a Reply