Spotlight: David Brock and the Art of Inspiration

I met David Brock in my first semester at Humber Polytechnic where he taught my introduction to creative writing course. While brainstorming for one of our assignments, I complained to him that I couldn’t write the idea that I had in mind because it was far too emo and angsty, and I was way too embarrassed to put it on paper. His response? “Who cares? Write the thing.”

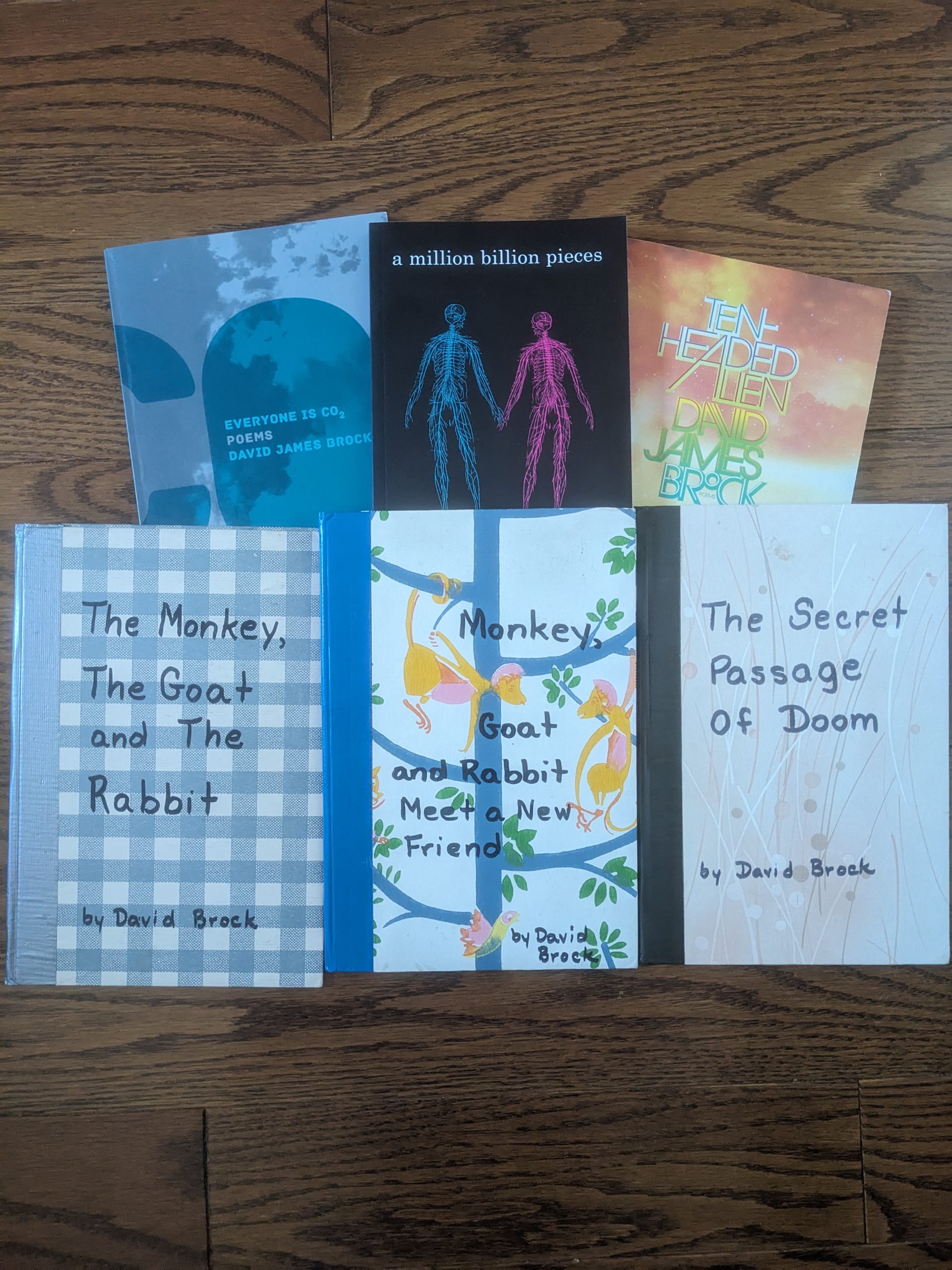

David is a screenwriter, playwright, poet, and opera librettist with national and international production history. He’s the author of two poetry collections, Everyone is CO2 & Ten-Headed Alien, and his play-opera hybrid, a million billion pieces, was nominated for five Dora Mavor Moore Awards after its premier as part of Young People’s Theatre 2019/2020 season.

In class, David likes to emphasize the importance of collaboration, not just with other writers, but with artists from all genres and mediums—literally anyone whose work inspires us to create. Not one to shy away from the tough stuff, David encourages us to write what we want, as long as we can do it safely.

Did you always know you wanted to write?

I suppose there was always a sense of it as a kid – that I’d make up stories and share them, though I didn’t quite know what that meant in terms of labeling myself as a writer. I think the first time I wrote stories down was in grade 3. Titles include The Monkey, the Goat, and the Rabbit—and its sequel, where they meet a new friend—and the dark adventure, The Secret Passage of Doom—projects created on a typewriter and bound in duct tape and wallpaper (pictured above). I still have these school projects shelved alongside my published books.

Through most of my teens, being creative took other forms: making movies on a camcorder with friends, writing screenplays derivative of Pulp Fiction in Hilroy notebooks, and trying to write rap and country lyrics – or bad perfect-rhymed poems about unrequited love—we all have these, right? Again, none of it ever felt like a career pursuit, just something I liked doing. I went and did a bunch of other stuff in the meantime (junior hockey, snowboarding, a zoology degree, traveling, working for vitamin companies), never thinking writing meant I was a “Writer.”

When did you decide to become a writer?

The big moment came when I started working backstage on plays in North Vancouver. I’d do this after a day job, and when I couldn’t get to sleep after a night at the theatre, that excitement had me thinking about actually doing this with my life, specifically playwriting. From there, I did what some folks reading this might have: I returned to school. I was called a mature student (I was barely 25!), and I was pretty motivated to justify what felt like a big life change at that point. I enrolled at the University of Victoria’s Bachelor of Creative Writing program, having never been there, and from then on, I was becoming a writer.

Though I don’t think school is necessary to become a writer, for me, that complete immersion into a writing life was made possible by the professors and students and reading and art and nature that I was lucky enough to engage with during that period of my life. The fact that it all made me happy validated the decision I suppose, even before some of my theatre work got produced.

What’s your main goal when you stand in front of a group of new writers to teach them something as subjective as creative writing?

I know everyone has a reason for being in a creative writing class, and sometimes I won’t know why. Sometimes, I don’t know why…yet. Sometimes, it’s none of my business. And that’s all okay. I want to try and help maintain the energy of the impulse, and I know that assignments and grades can sometimes feel antagonistic to that. Professors who are working writers understand this, honest!

Ultimately, I want to remain open in an effort not to ruin anyone’s experience. Too many people are discouraged too early, before they even have the chance to give it an honest try. However, I want everyone to be okay with learning from what came before: reading and consuming art widely gives us both a roadmap and a point of departure for our own practice. So I try to bring in as many influences as possible across form, genre, and even artistic discipline (my second years last year might remember being introduced to the somewhat obscure form of sprechgesang).

There are so many different sources for learning. How do we decide where and from whom to draw inspiration?

Ultimately, studying any art needs to be an individual experience, and I urge new writers to adopt a writer or artist they are excited by, to emulate in some way, and who they might eventually abandon as they develop new practices, interests, and inspiration. For me, this writer was American playwright, Sam Shepard. For any new writers, this is nothing I can bestow but maybe I can guide! At the heart of this is curiosity, and my belief that to be a writer, you should be a fan of at least some kind of writing.

How does the individual nature of studying art translate within the confines of a classroom where you can present only one lesson plan at a time?

I want to make sure I’m not the centre of things in a classroom. I can share my process and some of my perspectives, but I don’t demand that they become yours. I’ve met many writers, great writers, successful writers, and for the most part, how everyone gets to where they are happens on a different path and timeline. If I’ve helped a student feel like they are moving forward on their path, not mine, that’s a pretty successful outcome of sharing creative writing ideas with one another.

What advice do you have for writers who have too many ideas and can’t decide where to start?

Don’t worry about starting at the beginning. Let some of it be easy or even fun. So much of the writing process happens in a non-chronological fashion. Write the part that you can right now. The fun part. The exciting part. The part that keeps you up at night. Often, the part you couldn’t write wasn’t even integral to what you were trying to do, which is why it seemed so hard! Trust that. Sometimes those “too many ideas” all find their way into the same piece. But don’t worry about where scenes, lines, or ideas fit on a timeline when you’re in the process stage. These are product concerns. Try not to let product intrude too early. I know this is easier said than done, and I still struggle with seeing the movie on the screen or the book on the shelf before I fully work out my “moments.”

A lot of what we ultimately show a reader or audience is in the editing. We move things. We make new connections. We discover unconscious connections that our readers or audiences will think are brilliant—and they are brilliant. Practice comfort with the random discoveries and believe that over the course of a writing life, nothing is random when the muscle is working and the good stuff seems to come naturally. Take credit for it all later, as though it was your vision all along, but be humble enough to thank the moments and people who help you bring an idea into being at whatever point that happens on the timeline.

Brittany is a Creative Writing MFA Candidate at the University of Guelph. Her immediate writing focus is on developing characters who confront difficult, often buried emotions. As far as she's concerned, if she's not having an existential crisis, she's not living. When she isn't writing, she firmly embraces chaotic shenanigans, exploring Toronto in search of her next favourite meal or view of Lake Ontario.

Leave a Reply